Justin Bennett '23 has always loved physics. As he put it, “for my entire life I contemplated the complexities of the universe.” But during and after his sophomore year at Lehigh, he had an opportunity to get more serious about heavy ions, and pursue a passion for nuclear physics.

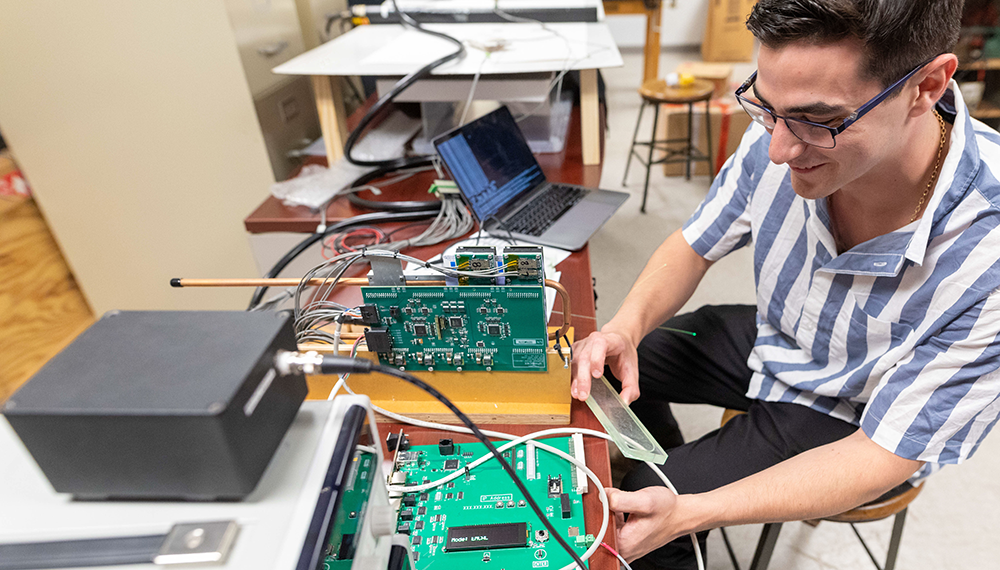

With the support of a Lehigh research grant, Bennett used available equipment in the physics lab to design an experiment using cosmic rays to test for light efficiency of the sPHENIX Event Plane Detector (sEPD). Bennett explains that sPHENIX, is an experiment under construction at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory onLong Island, N.Y., where sEPD will be one of many sPHENIX subdetectors used to better understand the heavy ion collisions occurring at RHIC.

Lehigh’s sEPD will specifically look at the orientation of the charged particles in the collisions at RHIC. Basically, sPHENIX will have many different detectors, all studying different aspects of the collisions specific to their engineering, he says. Lehigh is leading the construction of the sEPD, funded by a National Science Foundation grant.

For Bennett, the experiments are a way to better understand the universe. “Heavy ion collisions at high energy provide a possibility to address the many puzzling questions life brings us, from how the universe worked 13.9 billion years ago to how it interacts on the smallest of scales today,” Bennett wrote in his research abstract, “At Brookhaven, sPHENIX will be used to collect data from RHIC to better understand Quark-Guon Plasma, a new state of matter created at RHIC, “last seen microseconds after the Big Bang,” says Bennett. “Think of it as a sort of soup of subatomic particles.”

Bennett, who plans on pursuing a Ph.D. in the field of heavy ion physics, worked on cosmic ray testing at Brookhaven last fall. Cosmic rays, he explains, are the highly energetic particles that travel through space at relativistic speeds, or close to the speed of light.

“Although we never think about it, we are constantly being bombarded by highly energetic ionizing radiation,” he says.

Two years ago, Bennett took a course with Anders Knopse, assistant professor of physics, whose work includes experiments at the Large Hydron Collider at CERN in Geneva, Switzerland. Bennett found Knopse’s passion for nuclear physics inspiring. (He is also is working with Rosi J. Reed, associate professor of physics, who leads both the Lehigh heavy ion group and sEPD construction at Lehigh).

He applied for and received an approximately $5,000 grant from the College of Arts and Sciences which allowed him to develop and perform the benchmark tests for light efficiency of the tiles that make up the Brookhaven’s sPHENIX Event Plane Detector.

“It was an opportunity to grow as a researcher,” he says. “I wanted to dive deep.” On a broader scale, the experiment provides direct evidence that invisible cosmic rays are a real measurable quantity.

Bennett does not go halfway in physics. He says those who know him know that “physics is not just what I study, but it is a quintessential part of who I am.” Growing up in upstate New York, he was a piano-playing athlete who competed in football, lacrosse, and snowboarding, but he also “stared at diagrams and equations as one would a picture book."

"Not a day went by where physics and the unknown were not at the center of my attention,” he says. It was not surprising then, that at Lehigh, to which he applied early decision because he loved the campus, he quickly declared a physics major. The grant allowed him to construct a prototype cosmic ray test stand to determine light efficiency using muons that are produced by cosmic rays. The cosmic ray test was to make sure the sEPD didn’t have any problems with light efficiency, he explained. The cosmic ray test makes sure light goes through sEPD tiles. Brookhaven’s sEPD is designed to work in tandem with other detectors in sPHENIX when it becomes operational sometime in 2023. (sPHENIX is an upgrade from a previous experiment called PHENIX, which last took data in 2016). In his experiment to test for light efficiency, Bennett used muons produced by cosmic rays, “which can be thought of like a heavy electron,” with a mass about 200 times greater, he says.

Muons, which are the product of galactic cosmic rays, make up much the cosmic radiation that reaches Earth’s surface. Bennett’s experiment at Lehigh was set up using two paddle scintillators (made of luminescent material), which, like the scintillator material that makes up the sEPD, produce a flash of light when it interacts with ionizing radiation.

“My experiment was testing on sEPD, which, when sEPD is implemented into the overall sPHENIX experiment, will study the orientation of charged particles,” he says. “A muon that travels through about 1 cm of plastic scintillator might produce about a thousand photons, most of them in range of blue wavelength. These photons bounce around inside the scintillator until they escape or are absorbed. The light is then reflected down to a light guide which funnels the light to a photomultiplier tube, where an electrical signal is generated via thephotoelectric effect.

“If both paddles trigger within this extremely small timeframe, a particle is counted and data recorded. You can think of it like trying to if something went through the middle of a sandwich by connecting wires to the piece of bread, if both pieces felt a something go through it when it comes from above, it must of went through the meat in the middle.”

Last fall Bennett was able to learn from Lehigh graduate student Tristan Protzmann, at Brookhaven. “It was amazing using their equipment,” he says. “The scale of it is amazing.” Cosmic ray testing of sEPD at Brookhaven, he says, “is the exact same set up as at Lehigh, but much more automated, and multiple sectors can be tested at once rather than just one.”

RHIC is 2.4 miles in circumference and visible from outer space, notes Bennett. The RHIC beams of particles travel at 99.995 percent the speed of light, about 186,000 miles per second. It is the only operating particle collider in the U.S. and as of 2019 is the second highest energy heavy ion collider in the world next to the Large Haldon Collider at CERN. This past fall, Bennett was selected for a Conference Experience for Undergraduates (CEU22) award, to present his research at the Division of Nuclear Physics of the American Physical Society.

During the recent academic year, he says, “I continued to assist in the construction of sEPD at Lehigh,” and he also helped conduct cosmic ray testing over the summer. “I like to challenge myself, and like solving problems,” he says.

Not only does Bennett want to have an impact on the scientifically significant sPHENIX experiment at Brookhaven, but looking forward, he wants to become a communicator of science so that others can appreciate the universe as he does, and maybe get excited about heavy ions.

- by Wendy Greenberg

- Image by Christa Neu